Winnie, Norma, and Vincent

Winona Steel Ware Powers, my great-aunt, lived to almost her 104th birthday. Though her body failed, her mind stayed sharp. She would answer questions about any of the unusual decades of her life. I tried to ask questions every chance I had to visit with her.

Going back to the late 19th century, she liked to talk about her first job. It was at the Whitehall Inn in Camden. Her family lived on their small farm in Waldoboro, but by taking a job as a chambermaid, she could have room and board and earn money in Camden. The Whitehall Inn provided Winnie with her first step to independence. She remembered Norma, a waitress at the Inn, who also came from a home that struggled to have enough money for basics. Norma worked hard and was friendly but had a sibling who preferred using a middle name, Vincent, and Vincent seemed more interested in writing and socializing than working. Winnie had mixed feelings about Norma's sibling, Vincent.

Vincent could have worked at the Inn like Norma, but when Vincent came to the Inn, it involved reading poetry to well-traveled guests, chatting up the rich guests, sometimes playing the piano for guests, and only the briefest conversations with Winnie, Norma, or any other working staff. Winnie thought Vincent acted as if the staff was not worthy of attention.

Norma had one set of clothes for every day, one Sunday outfit, and the warm coat, hat, scarf, boots, and gloves absolutely necessary to life in Maine. For everyday clothes, Norma depended on using the uniforms provided by the White Horse Inn. Winnie had the same amount of clothing and pragmatic appreciation for her uniforms. Vincent had almost an outfit for every day and looked like a butterfly confident of landing on phlox.

The Inn allowed Vincent to drop in and play the piano or to read poems to the guests. Vincent's ethereal looks of a delicate limbed greyhound contrasted with Norma's solidity of a boxer. Not everyone knew Vincent and Norma were siblings. With passion in voice and words for poetry reading and discussions with the rich and well-connected guests, Vincent hardly even spoke to Norma.

One evening when Winnie’s workday had finished, she went to the room of the Inn’s soirées. Vincent had finished playing the piano and stood to recite a poem. The guests’ faces showed appreciation and one middle-aged woman did more than applaud Vincent. Winnie learned from Norma that the woman had decided to be a benefactor to Vincent. That guest had decided to pay for Vincent to attend college.

Vincent’s progress and move to college led Winnie to decide on making a move to a city for a job. She wanted to see more of the world than Midcoast Maine and wanted to earn more than chambermaid work paid, so she got a job with the Bell Telephone Company in Portland. There she earned enough to support herself and to help her younger sister, Idalene, pay for college.

Years in Portland equipped Winnie to move to work for a family on their estate in Connecticut. From managing the estate household, Winnie took a job that opened up working as a housekeeper for Cole and Linda Porter in their Murray Hill home in New York City. Cole Porter had more fame than Vincent had achieved, but he and Linda also had heartaches. Winne had never expected that fame and success would bring lasting ease and happiness; the Porters who seemed to love one another through all the ups and downs of their life together showed Winnie the truth about fame and success.

Sometimes when Winnie watched the love and kindness of the Porters, she thought of Vincent, full name Edna St. Vincent Millay, who also lived in New York City and still preferred the name Vincent to Edna. Vincent had published poems, ignored traditions, survived scandals, married, and had acclaim as a successful admired poet. Winnie did not want to be famous but she did wonder if she’d ever get married. She knew Norma Millay had ventured into the arts too; Norma traveled with a theater company that had performed on Broadway and had married.

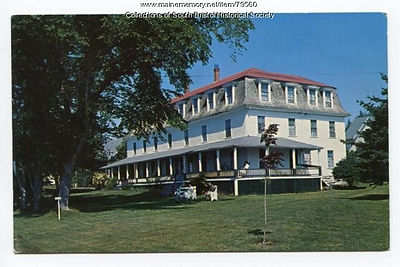

Winnie was 39 when she married Guy Ware, and they bought a large Inn, the Russel Inn, right on Christmas Cove in Maine, on a peninsula where the Damariscotta River comes into the cove. Winnie and Guy renamed the three-story inn the Christmas Cove Inn. Even through the years of WWII when people used black-out shades and worried about German submarine’s coming into Maine Cove, the Inn thrived with Winnie and Guy as owners, hosts, and managers.

Christmas Cove Inn

How often do we reflect on the people we worked with over the years in our earliest jobs, in any of our jobs? What did we learn from them and with them about how and where people belong? Do coworkers and acquaintances help us form goals for the future? How do we build relationships in the workplace that will lead to knowing where we belong?

In my first job, I worked with a slim attractive older woman who reached past me one day to pick up a box. I saw numbers tattooed on the underside of her left arm. I was only 14 and felt surprised enough to ask why she had a set of numbers as a tattoo. I knew about the Nazis. I read Anne Frank’s diary, Eli Wiesel’s, Night, and Corie ten Boom’s Hiding Place, but I’d never met someone who had been in a concentration camp. She talked with me every time we had a break time together. Never taking offense at my questions, she answered openly and taught me more than I learned in my history classes.

From that job onward, except for one job at a food stamp office, I did try to get to know my coworkers and to learn about them. At the Food Stamp office, I made one of the worst mistakes of my life by not trying to build a sense of belonging with coworkers. That will have to be for another blog post.

Virginia